At the end of September, Protocol Lab Research published a conference paper: Decentralized Hole Punching, which mentioned TCP Simultaneous Open as one of the hole punching techniques for TCP. I decided to investigate it. After explaining the technique, I’ll introduce an implementation example in C.

Normal TCP Communication and P2P Communication

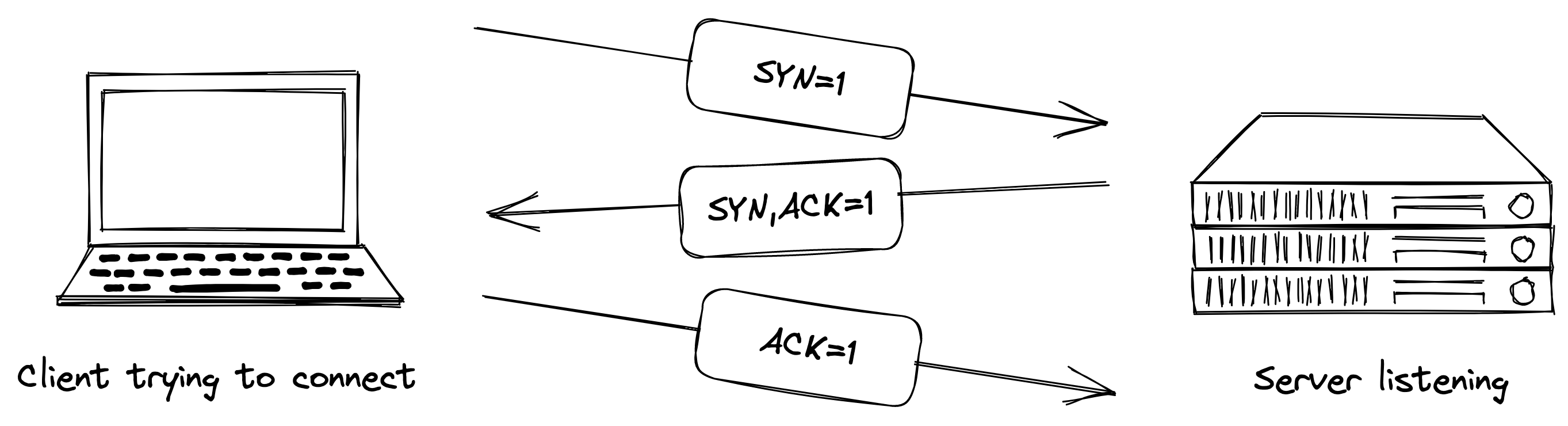

Normal client-server TCP communication is established through a Three-Way Handshake. First, the client sends a SYN packet to the server, the server responds with a SYN-ACK, and the client returns an ACK before data exchange begins.

The assumption here is that the server is not behind a NAT. This communication method works because the server always has an open port that the client can access. This assumption breaks down in P2P communication. Without going into the details of P2P communication itself, the most significant characteristic is the need to communicate between computers within local networks that I use daily. Being within a local network usually means being behind a NAT, and overcoming this barrier is what NAT Traversal and hole punching are all about.

Due to the nature of P2P communication, primarily used in video chats, hole punching is typically performed over UDP. The process is as follows:

-

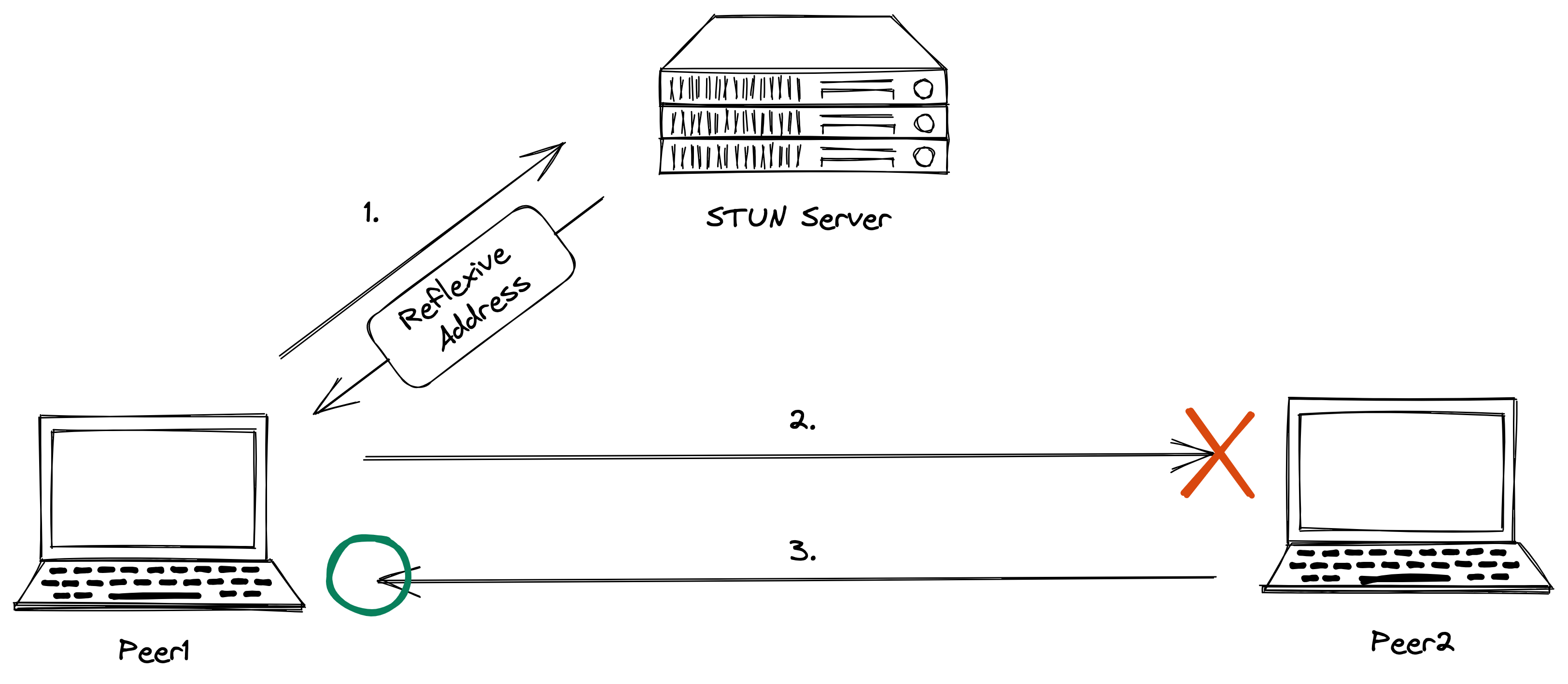

The initiator uses a STUN server to obtain its external IP address (called Reflexive Address) and port.

-

The initiator sends a packet to the receiver based on information obtained from a signaling server. At this point, the address is mapped to the NAT.

-

The packet from step 2 doesn’t reach the receiver and is discarded, but now the receiver sends a packet to the initiator.

-

The packet from step 3 reaches its destination normally because the sender’s port is already open. This enables bidirectional communication.

It’s important to note that if the external address for the STUN server and the receiver differ, this hole punching won’t work. This type of NAT is called Symmetric NAT, and in this case, the only option is to use a TURN server for essentially client-server communication.

TCP Simultaneous Open

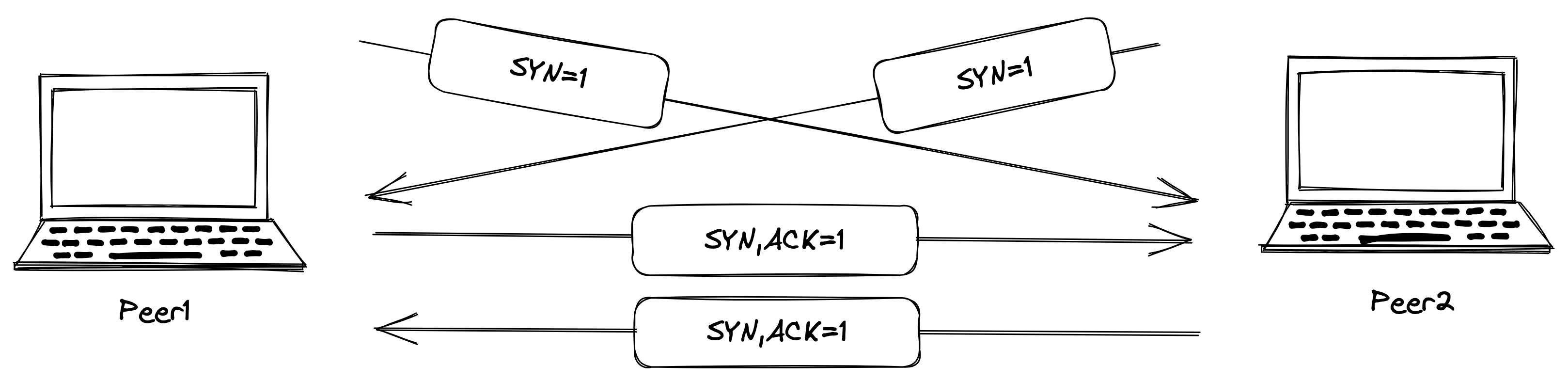

When attempting hole punching over TCP, the same method as UDP won’t succeed. As mentioned earlier, TCP principally uses a Three-Way Handshake, and if the initial SYN packet doesn’t reach its destination, the communication is reset and the port closes. However, there is a trick-like method to bypass the Three-Way Handshake principle and successfully perform hole punching. This is called TCP Simultaneous Open. I’m stubbornly writing it in English because I can’t think of an appropriate and natural Japanese translation, but if I had to translate it, it might be “TCP simultaneous connection”. I say trick-“like” because although the method seems a bit forceful, it’s actually a specification clearly documented in RFC793.

The “three-way handshake” is the procedure used to establish a connection. This procedure normally is initiated by one TCP and responded to by another TCP. The procedure also works if two TCP simultaneously initiate the procedure. When simultaneous attempt occurs, each TCP receives a “SYN” segment which carries no acknowledgment after it has sent a “SYN”.

(From Section 3.4)

The procedure is simple: after both parties obtain each other’s addresses, they simultaneously send SYN packets to each other. More precisely, they don’t need to be exactly simultaneous; it’s sufficient if one party sends a packet before the other party’s packet arrives. If successful, both parties then return SYN+ACK packets, and the communication is established.

In reality, timing packet exchanges simultaneously is very difficult and inefficient, so it’s hard to find actual implementations using this method. However, now that I understand it’s possible as a method, let’s try writing and running it.

Implementation

STUN Client

I’ll omit pasting the source code for the STUN server query client, but one important point to note is that the client also needs to bind the socket. If you don’t bind to the local port that will be used for actual communication attempts before querying the server, the connection may fail if it’s mapped to a different external port by NAPT, for example.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int descriptor = -1;

unsigned char buffer[BUF_MAX];

unsigned char binding_request;

memset(&binding_request, 0, sizeof(binding_request));

struct sockaddr_in sin_server, sin;

memset(&sin, 0, sizeof(sin));

memset(&sin_server, 0, sizeof(sin_server));

descriptor = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (descriptor < 0) {

printf("Socket creation failed");

return -1;

}

sin.sin_family = AF_INET;

sin.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

sin.sin_port = htons(atoi(argv[1]));

if (bind(descriptor, (struct sockaddr *)&sin, sizeof(sin)) < 0) {

printf("Failed to bind\n");

return -1;

};

sin_server.sin_family = AF_INET;

sin_server.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr(argv);

sin_server.sin_port = htons(atoi(argv));

if (connect(descriptor, (const struct sockaddr *)&sin_server, sizeof(sin_server)) < 0) {

printf("Failed to connect\n");

close(descriptor);

return -1;

}

printf("Connected\n");

*(short *)(&binding_request) = htons(0x0001); // Message Type (Binding Request this time)

*(int *)(&binding_request) = htonl(0x2112A442); // Magic Cookie (Fixed value to distinguish STUN traffic from other protocols)

*(int *)(&binding_request) = htonl(0x471B519F); // Transaction ID (Random value to pair up a request and corresponding response)

printf("Sending Binding Request...");

if (send(descriptor, &binding_request, sizeof(binding_request), 0) < 0) {

printf("Failed\n");

close(descriptor);

return -1;

}

printf("Sent\nReceiving Binding Response...");

if (recv(descriptor, &buffer, BUF_MAX, 0) < 0) {

printf("Failed\n");

close(descriptor);

return -1;

}

// 0x0101 at the first two bytes means this is Binding Response

// that being said the response is successfully received

if (*(short *)(&buffer) == htons(0x0101)) {

printf("Received\n");

int i = 20; // Data section starts after the header, which is 20 bytes

short attribute_type;

short attribute_length;

unsigned short port;

// Continuously read attributes in the data section

while(i < sizeof(buffer)) {

attribute_type = htons(*(short *)(&buffer[i]));

attribute_length = htons(*(short *)(&buffer[i + 2]));

// If the attribute is XOR_MAPPED_ADDRESS, parse it

if (attribute_type == 0x0020) {

port = ntohs(*(short *)(&buffer[i + 6]));

port ^= 0x2112;

printf("%d.%d.%d.%d:%d\n", buffer[i + 8] ^ 0x21, buffer[i + 9] ^ 0x12, buffer[i + 10] ^ 0xA4, buffer[i + 11] ^ 0x42, port);

break;

}

i += 4 + attribute_length;

}

}

close(descriptor);

return 0;

}

I used STUNTMAN as the STUN server here, but any STUN server that supports TCP will do.

$ ./a.out 44444 18.191.223.12 3478

Regarding the Binding Request mentioned earlier, the message format is predetermined, so referring to this might help understand it better. The response is also parsed according to the header size and flags clearly defined in the specification.

Hole Punching

This is the main implementation of TCP Simultaneous Open. The process involves creating a socket, binding it, and then connecting simultaneously using GMT timing.

Here’s the function that aligns the timing using GMT:

int get_remaining_msec() {

struct timeval my_time;

gettimeofday(&my_time, NULL);

struct tm tm;

gmtime_r(&my_time.tv_sec, &tm);

int sec = 60 - tm.tm_sec - 1;

int ms = 1000000 - my_time.tv_usec;

return sec * 1000000 + ms;

}

This function waits until both seconds and microseconds become 0 (xx:00.00), but if I don’t calculate down to microseconds here, the connect timing will be slightly off, and the connection will fail. Depending on the physical location of the computers, there’s already a difference with NTP time, so accurate timing is necessary.

Here’s the overall code using get_remaining_sec:

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

char* message = "Hello :)";

int misc_descriptor = -1;

int my_descriptor = -1;

int connect_res = -1;

my_descriptor = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (my_descriptor < 0) {

printf("Socket generation failed\n");

return -1;

}

struct sockaddr_in my_addr;

my_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

my_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr(argv[1]);

my_addr.sin_port = htons((unsigned short) atoi(argv));

struct sockaddr_in peer_addr;

peer_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

peer_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr(argv);

peer_addr.sin_port = htons((unsigned short) atoi(argv));

if (bind(my_descriptor, (struct sockaddr*)&my_addr, sizeof(my_addr)) < 0) {

printf("Failed to bind %s\n", argv[1]);

close(my_descriptor);

return -1;

}

int wait_for = get_remaining_msec();

printf("Waiting for %d microseconds\n", wait_for);

usleep(wait_for);

printf("Connecting...\n");

if (connect(my_descriptor, (struct sockaddr*) &peer_addr, sizeof(peer_addr)) < 0) {

printf("Connection Attempt Failed\n");

return -1;

}

printf("Connection Established\n");

if (write(my_descriptor, message, sizeof(message)) < 0) {

printf("Failed to send message");

return -1;

}

char* buffer = malloc(BUF_SIZE);

if (read(my_descriptor, buffer, sizeof(buffer)) < 0) {

printf("Failed to read message");

free(buffer);

return -1;

}

printf("Received: %s \n", buffer);

free(buffer);

close(misc_descriptor);

close(my_descriptor);

return 0;

}

The implementation itself isn’t too complicated, but I had some trouble preparing two computers not behind Symmetric NAT for testing. Originally having only one Mac at hand, I tried to use GitHub Codespace to save on server and VPS costs. However, after wasting about two days, I discovered that Codespace VMs are behind Symmetric NAT. I should have realized this when tcpdump on the Codespace side showed that packets weren’t arriving at all, but I doubted my own code more than the NAT type and wasted unnecessary time. In the end, I used Sakura Internet’s rental server, which was free for two weeks (as of 2022/11/3), to conduct the test. It’s questionable whether this can be called p2p communication since one side is a static server, but beggars can’t be choosers.

When you run the above code between appropriate computers, you’ll see a prompt like this:

Waiting for xxxxx microseconds

Connecting...

Connection Established

Received: Hello :)

Conclusion

The distributed hole punching method introduced in the conference paper at the beginning has already been implemented in libp2p, with a success rate of over 90% for UDP and QUIC, and lower for TCP (Reference: Libp2p Hole Punching). Well, the fact that they don’t give exact numbers suggests it’s not very high, and it’s predictable that there aren’t many cases of using libp2p over TCP in the first place.